This is the first post of the new Caucus Series: “Everybody’s talking about it at home, but nobody wants to talk about it at school.” It was co-written with Dara Savage. Check out these links for the continued conversation about how to be an antiracist in the classroom.

- 2nd post Beyond Woke

- 3rd post 22 Antiracist PBL Ideas

Ferguson

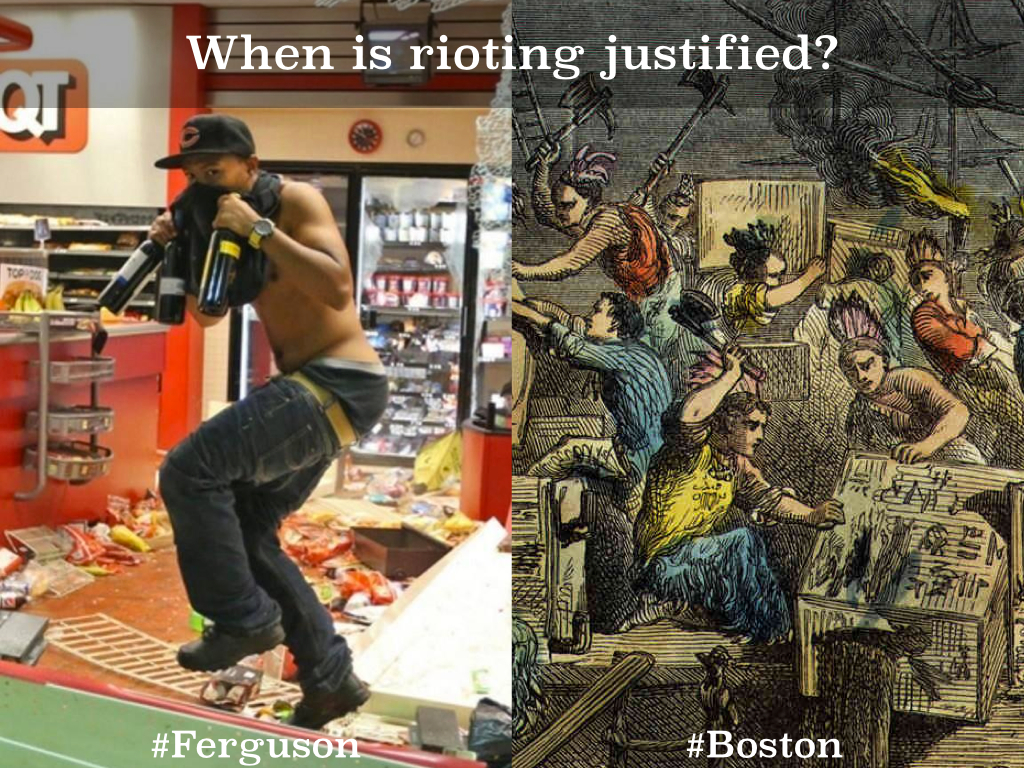

August, six years ago as the country was shook (again) by the police killing of an unarmed Black man, I (Mike) wrote a blogpost about the “rioting” in Ferguson. I used this image and asked open-ended questions about this current event compared to the Boston Tea Party. My blog did not have a huge following and there was no reaction for a couple of weeks.

Then on my first day back to school for mandatory professional development, my phone started blowing up as dozens of people submitted comments for moderation. I checked my stats and thousands of people had visited the post that day out of nowhere. As it turns out, a right wing blog associated with Glenn Beck had written about me and linked to my post. Fortunately I had comment moderation turned on as these radical, Tea Party members (the irony) wanted me fired and called me a communist among other nasty things.

The image and questions became

the image IN question.

That afternoon I received a phone call from a conservative, radio talk show host out of Philadelphia who wanted me on his program. Not wanting to be a straw man for them to roast for the rest of their show, I declined. Later that night I received a call from my administrator. The district administration wanted me to pull the post. Apparently one of these radical people looked at the city listed on my blog and called that school district. That district was not the one that I taught in, but they contacted my district administrators. They were fearful of political backlash.

I told my principal that I would consider it. I talked to some colleagues and activists, eventually deciding not to pull the post. I wrote it in the summer, at my house, on my computer, on my blog that does not represent anyone, but me. I have freedom of speech and was not going to be bullied by some wackos. The district was not happy with me, but never said another word about it because there was nothing that they could do. Needless to say, I had to watch my back due to my “disobedience.”

Not one of my students or their parents ever saw the blogpost to my knowledge. No one local ever complained to the school. But I never used this image or the topic in class either. I was now gun shy to talk about it. I still taught Civil Rights in American History class, but was careful not to get too “political.”

As we all know racism has not stopped, but it stopped being something emphasized in my classroom because I knew administration was watching me.

When I invited a state representative to our school to see our Monument Final Products, I was made to jump through so many hoops because there was a fear of what I might say to him. For the rest of my tenure, I was targeted and held back on getting real about race.

Sambo

In 2001, my (Dara) daughter was in the first grade. Like most first graders, she gave every detail of what happened during the course of the day including who got their cards flipped, who had to go to the nurse, what everybody had for lunch, and who got in trouble during the day.

On this particular day, my daughter came home and couldn’t wait to tell me about the funny story she heard during her enrichment class.

“Mommy, the story was so funny,” she explained.

She went on to tell me the story about a little boy and his mommy and daddy who lived in the forest. While they were in the forest they were chased by tigers. As a mom I thought she may have been a little confused because tigers aren’t typically in the forest, so I asked her to describe the little boy to me. Her entire expression changed.

“Mommy, he was black. Very black. And he wore lipstick and eyeshadow.” My heart began to sink because I was hoping she was not talking about what I feared.

“What happened after the tigers chased them around?” I asked.

“That was the funny part!” she said. “The tigers turned into butter, and his mommy used it for pancakes and the little boy and his mommy and daddy ate them!” There is no way she could know about this story unless someone had presented it to her. So just to completely verify, I asked her the little boy’s name.

“Sammy or Samuel….something like that.

“Was it Sambo?

“Yes! Mommy, that story was funny but I don’t know why that little boy had that makeup on.”

Little Black Sambo was written by Helen Bannerman and originally published in 1899. It depicts a little boy named Sambo and his mother and father, Mumbo and Jumbo, drawn in what would be considered a typical minstrel black face style with coal-black skin, exaggerated red lips, and huge white eyes. During the 40’s and 50’s there were complaints and even hearings in Congress to examine the depiction of Blacks in literature. Many libraries, states, and boards of education banned the story from their shelves because it perpetuated the negative stereotype of Blacks.

Warm Demander

Fast forward to 2001, when my daughter was one of the few children of color in her enrichment class, and this text was presented to them. I took off the next day and went to school with my daughter. I stopped by the office of the Superintendent who I had known for decades. I told him about the situation, and he understood my outrage. I told him that I would like this instance documented in the teacher’s file. When I left his office, I went to her classroom.

Her justification for using this book was that she was discussing fairy tales with the children. “I grew up with this book and didn’t see any harm,” she said. After explaining to her why these images are offensive, how promoting these images to impressionable white minds and Black minds alike was simply perpetuating the stereotype of “black buffoonery”, providing her with a plethora of examples of actual fairy tales that were more culturally sensitive, and probably, in her mind, causing all kinds of trouble, I returned to the Superintendent’s office to let him know how our discussion went. I asked him if I needed to bring this to the attention of the school board, and he told me that it would be handled and there was no need for that. I trusted him.

After that incident, I had to rethink the way I explained this imagery to my daughter. We talked about it on various levels as she grew up.

She got to the point where she said, “I hate those extra black faces. I don’t ever want to see them again.”

I explained to her that they were a part of our history that cannot be erased and that learning more about them would lead to a better understanding – which was the catalyst for my Black memorabilia collection…imagine that.

Cheers to the Troublemakers!

Since the Ferguson blogpost, I (Mike) have not been silent about race in my classroom or online, but this incident is always in the back of my mind. Sometimes I tend to hold back and be careful not to offend.

It’s time for me to move on from my fear and uncomfortableness. I now realize that for Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC), it is almost always the “wrong” time for them to speak about race. If I truly care about equity, justice, and anti-racism, then I am obligated to speak up, no matter my comfort level. Writing this blog post is part of it; I’ve written a lot of blog posts over the years, and this one is the first that’s hard to hit publish on because of all of the backlash of the past, being viewed as a “troublemaker”. So cheers to the troublemakers!

I used my white privilege to avoid talking about race if it would be perceived as political. I am tired of being silent.

There has been a huge movement this summer in response to the murder of George Floyd. Many teachers are looking deeper into racism for the first time. Maybe you are afraid like I was to get too deep into current racial tensions in your class. Maybe you are afraid that you will make a mistake like Dara’s daughter’s teacher did. What is the appropriate way to discuss important, but controversial topics at school?

This is the first post of the new Caucus Series: “Everybody’s talking about it at home, but nobody wants to talk about it at school.” Stay tuned for the continued conversation about how to be an antiracist in the classroom.

This post was co-written with my friend and English teacher extraordinaire, Dara Savage.