Many teachers use online timers as a management tool to keep students focused for a set amount of time during a specific activity. Sometimes students have to complete a task under pressure and they race furiously to get it done. Some students may feel overwhelmed during this kind of timed exercise. Others seem to thrive. I have nothing against this use of them, but what if we “flipped” the use of timers?

What if we timed ourselves, the teacher, instead.

Recently I observed a former colleague, Nate Langel, teaching some high school freshman about polar and non polar molecular bonds. Students started by performing a series of experiments about the properties of water, oil, and soap because ABC (action before content). Then they worked through a module consisting of online videos, key vocabulary definitions, and science concepts.

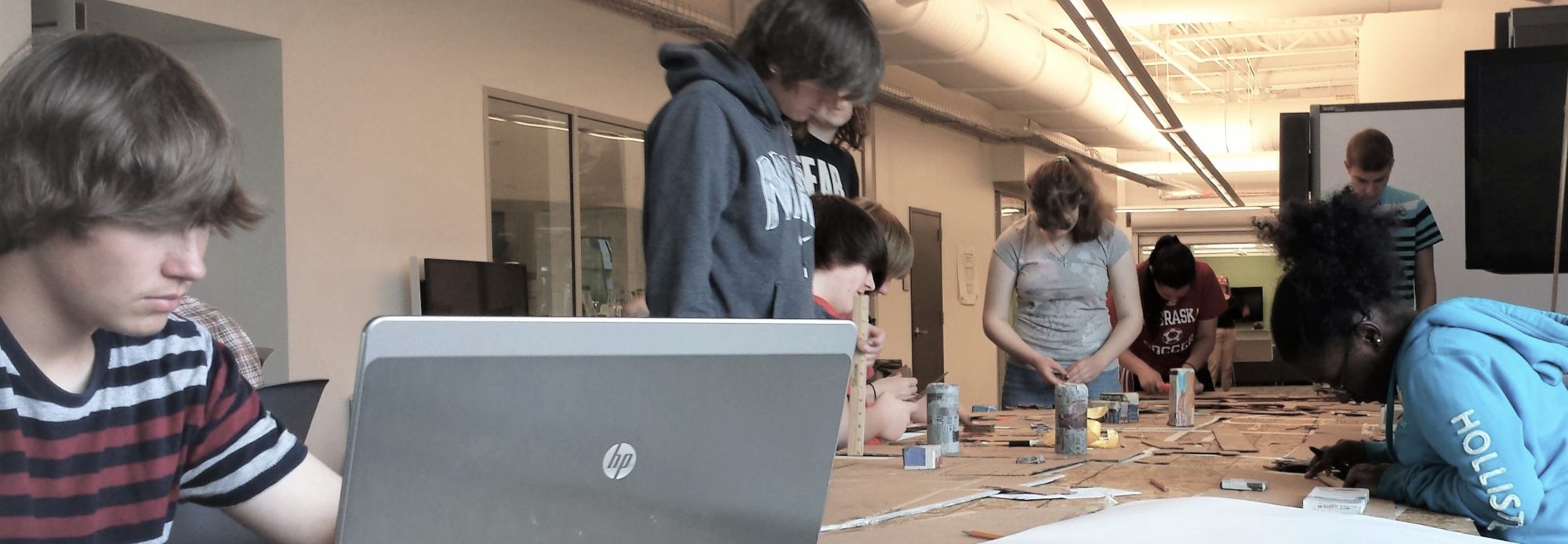

Nate teaches a PBL class and uses small group workshops to deliver instruction. As students were working, he rotated around the room pulling small groups of 3-5 kids aside to a whiteboard or window and drew some diagrams of molecules to make sure students understood the science behind the experiments.

But before he started, Nate did something that I have never seen before. He opened a timer on his phone, told the students, “ok, I am setting this for 5 minutes,” and then handed his phone to a student to time him as he lectured. I thought it was brilliant.

Besides using timers to “keep students on track,” how many of us have considered timing ourselves? I asked Nate about his process later and where it originated from. He told me that students always complain that he talks too much and that they need more work time (says every student ever). While he admitted that he didn’t necessarily agree that they needed more time vs. using the time that they have more wisely, he organically started timing himself to honor the student feedback.

The first thing that I like about this approach is that it deals with a common classroom management, engagement, and learning problem: teachers like to talk and we do it too much.

When we are dominating the classroom with our voice, then students’ voices are minimized.

Lectures get boring when they drag on and on. Students discussing content with each other is better pedagogy.

So timing ourselves puts a healthy pressure on the teacher not to talk too much. It increases student focus because they are not zoning out thinking, “Here we go again. I am going to have to listen to blah, blah, blah, for 30 minutes.” Rather the teacher can motivate students to commit to concentrating for a short period of time rather than a long lecture. Talking with a small group, instead of whole class is another crucial factor. Now it is an interactive conversation checking for understanding, instead of a lecture.

A closing thought from Nate, who like me is a huge advocate for student voice and choice. Sometimes we get so passionate about student-centered learning that direct instruction gets a bad name. We both agreed that it is absolutely essential for students. Direct instruction just needs to be done in ways that are effective with students: just in time, interactive, small groups, and in short bursts of time.

Questions? Interested in SEL and PBL Consulting? Connect with me at michaelkaechele.com or @mikekaechele onTwitter.

Pingback: Sharing Diigo Links and Resources (weekly) | Another EducatorAl Blog