Misconceptions of Student Voice and Choice

An old misconception of Project Based Learning is that PBL is all student choice and inquiry without any teacher input. Students choose any topic they are interested in and then do whatever they feel like with it; basically unschooling on a large scale. This misconception paints the teacher as an unneeded bystander with little role in the learning. Teachers envision chaos when they consider this in their classroom. They correctly assumed that this distorted view of PBL won’t work for their students.

Today most teachers realize that is not how PBL works, but rather it is a framework for structured student inquiry into important content standards through meaningful experiences. PBL and inquiry should include active teacher input in the design and implementation of the learning activities. Yet an offshoot of the old chaos misconception remains. It rears its ugly head when educators debate whether direct instruction or inquiry is the best pedagogy.

Some teachers reject inquiry wholesale using research claiming that direct instruction is more effective (this research is usually limited to results from standardized test scores). An example of this is the “science of math” movement arguing for explicit, direct instruction of math algorithms, even when students don’t understand why they are doing them.

Sometimes deficit thinking is hidden in critiques of inquiry methods with statements such as “My students can’t learn content without me explaining it to them first.” The real meaning of this quote is that this teacher does not believe the students in front of them can think critically on their own. It is the same kind of “pyramid” thinking that misuses Bloom’s Hierarchy to limit students to the lowest levels of basic knowledge acquisition.

The direct instruction vs. inquiry debate falsely assumes that they are mutually exclusive.

Too Much Lecturing

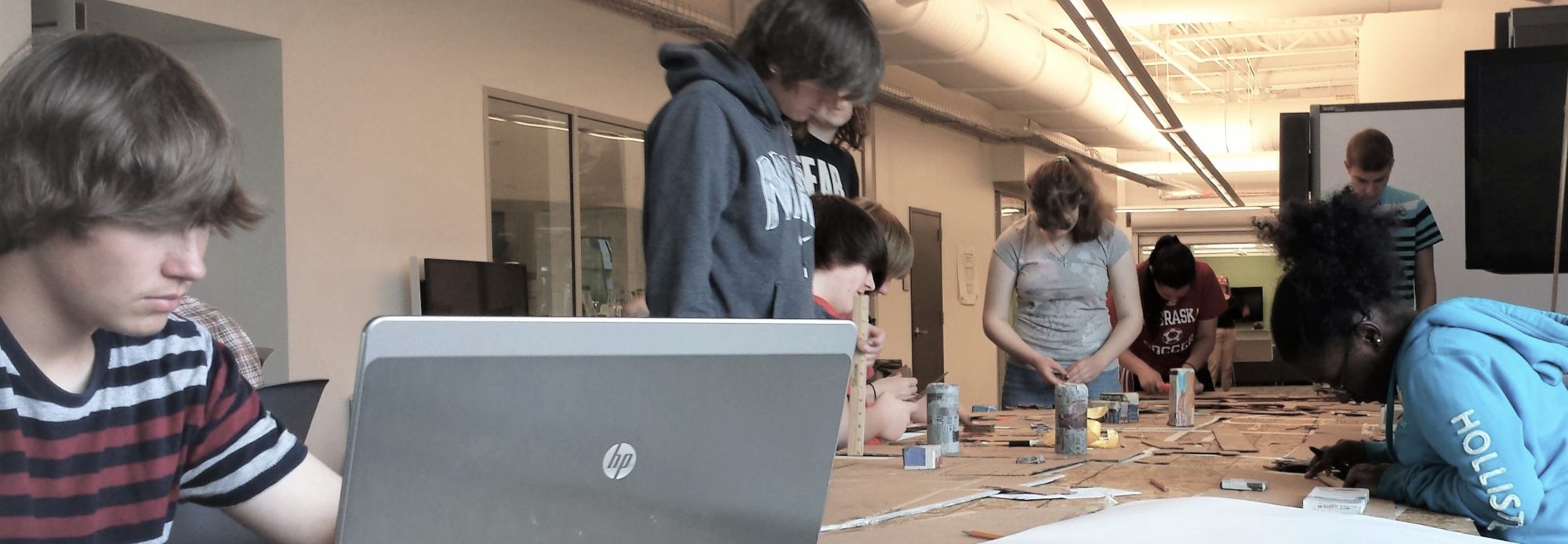

I am a strong proponent of student centered learning and the inquiry process, but that does not diminish the teacher role at all. Instead it shifts the teacher role from talking in the front of the room all hour to coaching small groups. I have realized that my critique of the traditional classroom is not centered on direct instruction, but the more specific technique of whole class lectures.

I am not saying that lectures are inherently bad and should never be used. My issue is when lectures, slides, and note taking are the predominant pedagogy in the classroom.

My educational philosophy has always prioritized active learning: “Whoever is doing is learning.” The work in a lecture is primarily found in the preparation, which is entirely done by the teacher. Passive note taking by the students listening can be mindless. We need students who are actively involved in their learning rather than copying down words to concepts they may or may not comprehend.

The problem isn’t direct instruction, but classrooms dominated by teacher lectures and powerpoint slides leaving students as bored audiences with no personal connection to the content.

Lectures are not effective for many students. In my math class, all of the proof that I need of lecture’s ineffectiveness, is how many students raise their hand for help after I just did three example problems on the board that they copied into their notes. Students are doing what they are told, but have no comprehension of the what or why behind it. If a new problem is slightly different, most of them are at a loss with how to attack it.

Workshop Model of Instruction

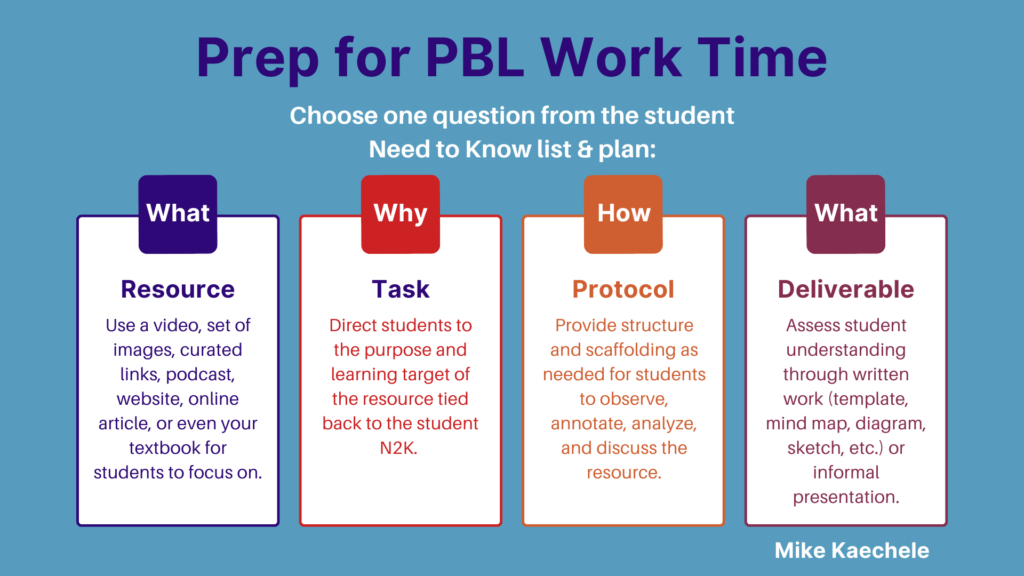

Beyond whole group lectures, there are many other effective ways to utilize direct instruction in a workshop model. In Project Based Learning, the teacher can choose one Need to Know from the list of student generated questions to focus on for the day. Then give students:

- Resources to supply direction

- Task to explain the why

- Protocol to provide structure

- Deliverable to keep students accountable

Students can learn content from many sources beyond a teacher explanation. Use a video, set of images, podcast, website, online article, or even your textbook as the resource for students to focus on. Mix it up so students see different forms of media or give them a menu of choices.

Next student need the task for the day. Why are they using this resource? What is the purpose or learning target that they should achieve? Be clear about what the takeaway should be.

Use protocols such visible thinking routines, SIOP, or eduprotocols to structure and scaffold how students interact with the resource. Protocols teach students how to dissect and analyze different sources. They also structure academic conversations and dialogue between group members. Experiment and choose 3-5 that you repeat throughout the year. With familiarity of the process, students will excel at using them.

Finally require a deliverable at the end of the hour. This could be a mind map or filling out a template. Or it might be presenting their findings to their group or the whole class. Many protocols have deliverables built into their procedures so this is not an extra step.

Start by asking yourself: What direct instruction method besides whole group lecture could I use to teach this concept?

During work time the teacher can push into groups to check progress or teach a mini-lesson or pull out students based off of formative assessments as needed. Pulling out students is an excellent way to differentiate providing support only to those who need while allowing the rest of the class to work in groups on their project.

PBL and inquiry can and should include direct instruction from the content expert, the teacher. The difference is that it primarily comes in the form of small group coaching, rather than large group lectures. Formative assessments allow the PBL teacher to focus their coaching on those students with gaps through a combination of questioning and direct input as necessary.

Learn with me!

Are you interested in professional development for your school on how to integrate SEL or implement PBL? I would love to have a conversation on how I can help. I am now scheduling summer workshops and book studies. Check out my workshop page or drop me an email at mikejkaechele@gmail.com. I would love to chat and co-plan meaningful PD for the educators at your school.

Would you like to explore more deeply how to integrate SEL into daily classroom activities? Check out my book below for tons of practical ways that can be immediately implemented in any classroom.

Pulse of PBL